Via Rail’s The Canadian, making its way towards Winnipeg through northwestern Ontario.

For a time it was the Chicago of the North, a prairie colossus swollen by immigration and driven by the power of the threshing machine and locomotive. From its position at the confluence of the Red and Assiniboine Rivers, Winnipeg seemed destined to funnel grain to the hungry nations of Europe, and to become a metropolis for millions.

It hasn’t quite worked out that way– not yet– for for Manitoba’s capital. Other western cities took their share of the grain trade, or grew larger on oil and trade with Asia. Today Winnipeg’s population is about 728,000, and the city’s broad avenues and early 20th Century architecture make for good sight-seeing. I was in Winnipeg in mid-November for the Canadian Forage and Grassland Association conference (more about that in future posts.) Though the meeting was held downtown, near the corner of Portage and Main, I was keen to see what I could of the province’s tall grass prairie heritage.

Winnipeg’s ornate and beautifully-restored Union Station, officially opened in 1912.

This swath of southern Manitoba was once covered by chest-high stands of prairie plants and grasses, part of a tall grass prairie that sprawled over 1.5 million acres from Manitoba south to Texas. In some regions, the cover grew so high people were literally submerged within a forest of grass. An early Spanish explorer said a man on horseback could easily become lost in the dense vegetation.

Now, with temperate grasslands the world’s most endangered ecosystem, I wanted to learn a bit about what was lost, and maybe see what remained. Granted, mid-November isn’t the best time to see the prairie in its finery, but after my train rolled in on Monday morning, I hoofed it over to the Manitoba Museum hoping to take in its Grasslands Gallery. The bad news is the museum is closed on Mondays, and that was my only free day before the conference. The good news? It’s a lovely walk along the Red River.

A good summer destination would have been the city’s Living Prairie Museum: 32 acres of remnant tall grass, squeezed between housing and an industrial area. The land was saved (by one vote) by a far-sighted city council in 1971. Now the museum is home to over 150 plant species, countless insects, birds, and animals, large and small.

A major draw is July’s Monarch Butterfly Festival, but the museum also plays host to planting workshops, native plant sales and school tours. During the winter visitors snowshoe the grounds on Sundays, or attend an annual lecture series.

July and August are peak months for visiting. “Now that more people are aware of how rare tall grass prairie is, they’re coming to see it with more interest,” says museum director Sarah Semmler. “We get people from the local area who have never visited a tall grass prairie. We have people coming from Australia, Europe, the U.S. who have an interest in grasslands, and people from across Canada doing road trips.”

As for four-legged visitors, the largest these days are white-tailed deer. “Historically, we had bison on the site. We have the wallows to prove it.” Semmler adds.

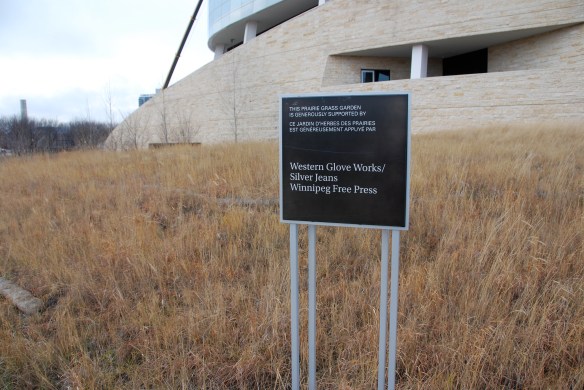

The Canadian Museum for Human Rights rises from a surrounding five-acre planting of prairie grasses and wildflowers.

In recent years Winnipeg has worked hard to retain and display its botanical roots. On my way out of Union Station, I noticed planters featuring prairie grasses. At the nearby Canadian Museum for Human Rights, the glass superstructure swirls out of native limestone, surrounded by prairie grasses.

Native Plant Solutions, an arm of Ducks Unlimited Canada, sowed the mix of native prairie species around the museum in 2014. The job included installing about a foot of topsoil atop a compacted building site – hardly ideal ground for such deep-rooted plants – then planting about a dozen species, ranging from towering big bluestem and native wild ryes to short-growing buffalo grass and showy prairie clovers. “It’s a shotgun approach,” manager Glen Koblun says. The goal is to mimic a natural stand, with a mosaic of vegetation that adapts to local conditions.

Thanks to the limited top soil, he adds, “you’re not going to have six-foot bluestem, but you will have it waist high, or so.”

Meanwhile Native Plant Solutions has been sowing prairie plants and landscaping everything from retention ponds and utility corridors to residential areas. Even with occasional managed burns, prairie grasses require about a third to half the upkeep of conventional sod. Koblun says municipal authorities like the idea of saving taxpayers’ dollars and at the same time restoring native species.

The museum’s landscaping was backed by private and community sponsors.

Koblun reckons the firm has replanted about 600 acres in the provincial capital. So while only the slimmest fraction of that original ocean of grass remains, these new plantings – and remnants such as the Living Prairie Museum – mean the region’s botanical heritage is not forgotten. Much of the domain of the prairie grasses may have been usurped by concrete and glass. Yet the grasses persist, a reminder of what has been lost, and a promise that recovery is still possible.

-30-