Mackenzie Foy and Matthew McConaughey, backed by 500 acres of corn on the set of Interstellar. (Bonus trivia: these scenes were shot in southern Alberta.)

In Interstellar, Christopher Nolan’s dystopian tale of the near future, the settled parts of the world seem like a vast cornfield. The Earth is dying, and farmers are hard-pressed to keep up with the demand for food. Beyond the towns and cities, corn sprawls to the horizon, the tasseled ranks broken only by the automated harvesters. Just over the horizon, a dustbowl is expanding, and a spreading blight threatens crops.

There’s more to Interstellar than corn and dust storms, of course: there’s the search for a new home for humanity, the subsequent journeys to distant planets, and Anne Hathaway in a space suit. This being Nolan, there’s a lot of playing with time and space (for a similarly ambitious warping of the usual narrative approach, see Dunkirk.)

But the image that sticks with me most is the planet of corn. In some ways, Nolan’s vision is prescient. My own province, Ontario, is increasingly a landscape of urban sprawl separated by acres of row crops, especially corn and soybeans. Squeezed out is the acreage once devoted to hay and pasture – the agricultural grasslands that are still the core of my own farm.

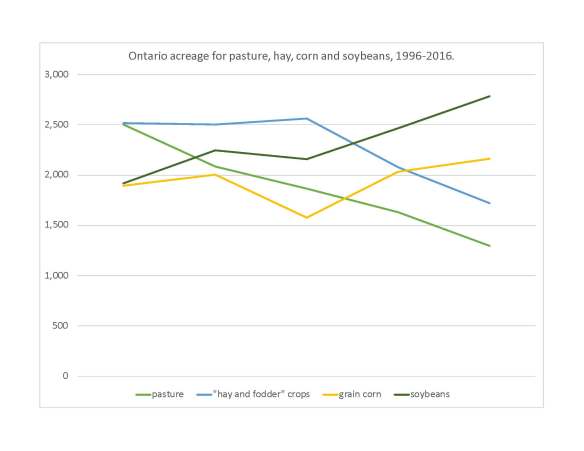

If you look at this graph, you can see the changes in the past 20-odd years. Crops are generally up, while grasslands demonstrate a solid downward trend. Pasture losses are the most striking: “tame and seeded” pasture (generally newer, better managed fields) fell by 21 per cent in just five years. “Natural” pasture land – land that hasn’t been ploughed in decades, or more – declined by 20 per cent.

Graphing the trend: more corn and soy, (yellow and black lines) fewer acres of pasture and hay (green and blue lines.) The vertical axis, left, represents thousands of acres, so 2,500 is 2,500,000 acres.

This change is the cumulative result of thousands of on-farm decisions, and I don’t want to knock fellow farmers for doing what they think is the best. When crop prices are good, it seems like a good idea to plough up pastures and grow higher-value crops. Once fences are torn out to make bigger fields, the cost of re-establishing perimeter fencing becomes a deterrent to shifting back into livestock. And after a generation or two with few or no cattle or sheep, the know-how and on-farm infrastructure for livestock is lost. There’s a cultural issue, too: livestock farming is a slow-and-steady business, one that builds over years, and generations of animals. It’s an approach that seems out of step in a business environment that values the quick payoff.

We need grain, and someone has to grow it. But the overall trend to less grass and more annual crops is a worrisome one. Well-managed hay and pasture stands have benefits that extend well beyond the farm, or any single farming year. They feed the soil, store carbon in the ground, limit erosion, help improve water quality, and maintain habitat for wildlife.

Crops, on the other hand, tend to make withdrawals from the soil bank over the long term. One of the remarkable figures I’ve seen this past year was a 1949 soil report on Essex County farms. Essex is in far southwest Ontario, and today it’s high-value cropland, a mix of horticultural and vegetable crops and the more common cash crops, including corn and soy. In the late ‘40s, when the area featured more livestock and forages, typical soil organic matter levels averaged more than six per cent. Now they’re almost half that.

It’s a startling decline. Each per cent of organic matter represents about 20,000 pounds per acre. Since organic matter is crucial to soil health and quality, that loss is a major weakening of the earth we rely on.

So on your next drive to the city, have a look at the landscape stretching along the highway. Perhaps most city dwellers don’t distinguish a corn field from cattle on pasture – for them it’s all farmland. But I expect the readers of this blog might appreciate the benefits (aesthetic and otherwise) of a more diverse rural landscape. If the trend to less perennial grass and more annual cropping continues, that view will become less diverse, more Interstellar.

-30-